What Rough Beast? - Interview with Byrn Hammond - Simulcast on Black Gate

Blazing New Trails: The What Rough Beast? Campaign, and an Interview with Author Bryn Hammond

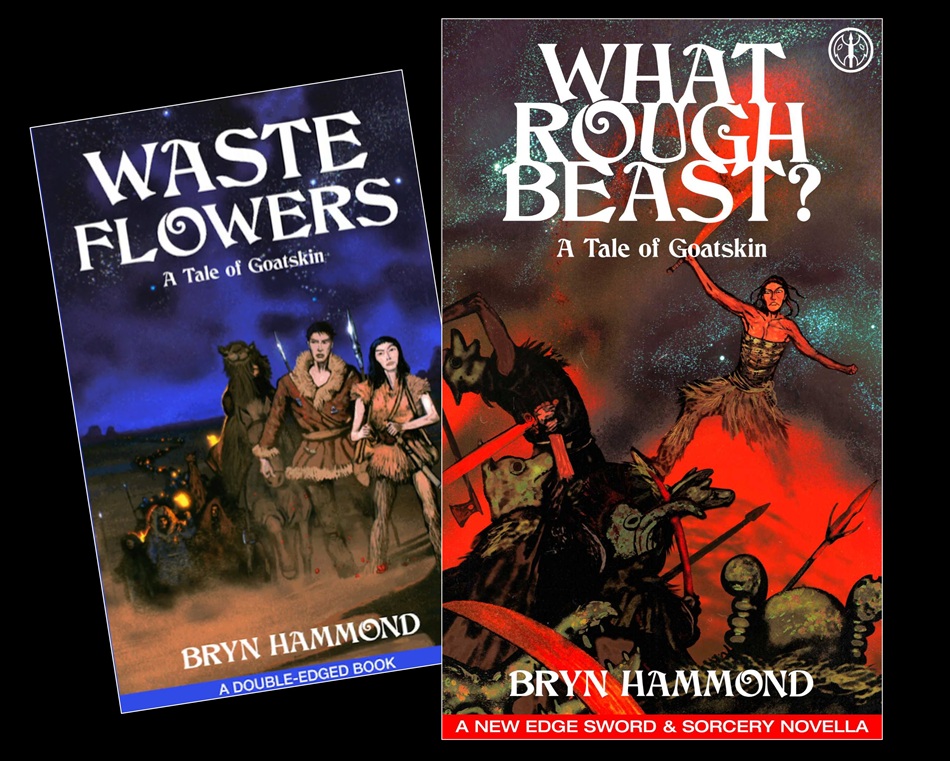

Waste Flowers and What Rough Beast? Tale of Goatskin, written by Bryn Hammond, both with cover art from Goran Gligović[/caption]

Waste Flowers and What Rough Beast? Tale of Goatskin, written by Bryn Hammond, both with cover art from Goran Gligović[/caption]

Black Gate has been tracking the inception and growth of New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine, starting with Micheal Harrington’s 2022 interview with Oliver Brackenbury (champion and editor of NESS), through 2023 with NESS's first two magazine releases (also Mele’s review of #1), and then into 2024 with NESS’s first book “Beating Heart and Battle Axes and its two-novella combo book Double-Edged Sword & Sorcery, and (deep breath)... most recently... NESS's publication of a NEW Jirel of Joiry! (2025).

NESS crowdfunds 4 New Novellas (link)!

Surprise, NESS continues to blaze flaming hot new trails! Starting this September 9th 4PM and running through September 30th, NESS pitches four novellas. The first advertised is What Rough Beast?, written by Bryn Hammond (with cover art by Goran Gligović, and interior illustrations by Linnea Sterte). As shown in the cover images above, this first novella is another Tale of Goatskin and has the same cover artist as Waste Flowers, Goran Gligović, who was featured in a mini-interview on Black Gates' previously.

Waste Flowers

Goatskin the goat nomad and her bandit love Sister Chaos guide merchants from Samarkand across the Gobi desert to the Mongols. But their caravan veers from one weird assault to weirder and worse. Who is behind this grotesquerie? Will they lose their way, or even lose their minds?

What Rough Beast?

Among the yak nomads, rowdy, restless young have thrown themselves into a cult of were-beasts ridden by unknown spirits, and they stalk Goatskin. They feel evil: evil by the lights of the intruder Temple, or by the banned old beliefs? And the shaman Goatskin searches for – a sad old man who set off on a quest his people call insane – what beast does he impossibly grapple? In the starry high meadows, what inhabits the night? Whose evil?

The other three novellas in the campaign promise wondrous, contemporary adventure, as per NESS's mission. But here we highlight Bryn Hammond's contribution. Learn her muses and motivations, why she splatters paint on canvases, and learn why you'll want to follow Goatskin into the haunted Gobi desert and beyond as she battles seriously weird, undead armies and dragons!

Read this, learn inside scoops, follow Goatskin!

"The giant dragon’s skull sticking out the cliff was helmet-like with thick bone armour, three horns of escalating size up its muzzle, flared bone at the neck, a low-slung heavy jaw toothed in irregular troughs and ridges, somewhat like a monstrous fish Goatskin and Qi Miao once fought in the underwaters of an ancient sea that lay beneath Qaidam Marshes.

Goatskin exchanged a grimace with Qi Miao.

Spine peeled from the sandstone. It left an indent of itself but did not disturb the cliff. Rear of their party, two more dragon skeletons shifted from the cliff, as quiet as sand from sand, and stalked forwards. Three snouts with nostril holes high in the air, then diving on snakes of neck bones to push towards the knot that had been the string of camels. They ignored the humans, who scattered to either side of the canyon and hugged rock. Camels, unattended and terrified, tied themselves up into a snarl of confusion in their tethers. Bony jaws swiped at them and snapped, choosy about food, upon their humps…" - Waste Flowers p28

1. What is “What Rough Beast?” Is this novella a sequel to Waste Flowers? Please introduce new readers to both.

What Rough Beast? does follow on from Waste Flowers, but in the finest S&S tradition, each novella is a standalone. You don’t need to read in order.

In Waste Flowers my Goatskin and Qi Miao visited Tchingis Khan on the high steppe, on the eve of his wars with China. In What Rough Beast? the wars have started, and my two pursue the consequences of their different attitudes towards those wars. Tchingis Khan comes between them, I’m afraid.

That’s the historical setting. Against it, Goatskin is on her own hunt for things that matter to her, in the low sword & sorcery way, and dodging the bigness of history.

2. You have a fascination with Mongol, Asian history. Can you explain your historical Amgalant fiction and any connections to Waste Flowers? Can you explain your muse?

I have a huge corpse, distributed about notepads and docs, called Scavenger City: my never-to-be-written third book of Amgalant. There is a wisdom, as I can aknowledge a few years after the fact, in abandonment of a work that grew too gigantic for you; in recognising its finished state, because as a person you are years away from the one who wrote those first two books (she was the better person, and certainly more hard-working). I am left with a sprawl of notes and raw material and drafts, filthy rich for scavenging.

I still have things I want to say. If I didn’t, this clinging would be unhealthy. In truth I’m in grief for that third book (never won’t be), but I can pluck out tidbits for stories and that’s going to keep me happy for a fair while.

On the other hand I want to move away, as well. Waste Flowers leaned heavily on Amgalant; I couldn’t resist writing Dead Jamuqa. You asked about my muse? I’ve called my muse ‘Jamuqa’ for several years, since I wrote his death: he grew so talkative in my head, so conversible. He almost took over those books, except that Temujin, Tchingis Khan, can stand up to him, meet him as an equal: their ambiguous friendship-enmity – love and rivalry – had been the backbone of Amgalant, as it is of my source the Secret History of the Mongols; I revisited them in Waste Flowers, and don’t say I won’t again. Yet with What Rough Beast? I am getting more independent, letting Goatskin go off on her own sweet tangents.

3. Any inside scoop we can share exclusively here? What is something most people do not know about you or your writing?

A future story I’m excited about, that I haven’t mentioned in public – that I haven’t started, either, but it came to me in a swoop, scavenged from the corpse of Scavenger City; it’s for a project not yet announced. It’s to be called ‘The Unicorn’ and it lets me tell the tragedy of Tchingis Khan’s late years, in a short space, a short story space. Tragedy with an upturn at the end, a note of grace – because the most moving tragedy has; and it’s got to be the finest goddamn story I can write.

‘About me’: oh hey, I want to let people know why I don’t or rather can’t do voice interviews, since I haven’t said this elsewhere: I’m neurodivergent with a speech disability. I so enjoy the story discussion panels NESS hosts, but it’s just not a possible thing for me to join in.

4. The only “Steppe writer” I know is Harold Lamb. Can you tell us about the authors who inspired your focus?

I don’t have fiction writers who led me to a focus on the steppe. My roundabout journey began in old travels in other nomadic cultures: from the film Lawrence of Arabia into Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, to Doughty’s Arabia Deserta and Wilfrid Thesiger. Travels are great, but primary sources are better: to get at early Arabs I acquired a secondhand of Ibn Ishaq’s Life of Muhammad; 800 pages of first-hand daily life, attitudes, battles, tribal politics, verse, of warlike women, warlike men, career poets in spats with other poets. I admit I’ve hauled a couple of incidents out of Ibn Ishaq and smuggled them into Amgalant.

A travel book first took me to the steppe: the Dover edition of Huc and Gabet, Travels in Tartary, Thibet and China, 1844-1846. French priests, for whom the Mongols live in a Biblical simplicity they at least admire, where others old travels are rude. Another Dover edition, the Yule-Cordier annotated Marco Polo under two fat spines, the bulk of which is small-print historical footnotes that give the width of knowledge circa 1903.

The first history of the steppe I read was René Grousset, whose birth and death dates are about a decade before Harold Lamb’s. I cannot say fairer than the forward to the 1970 reprint of his Empires of the Steppe: ‘majestic sweep and grandeur ... the intellectual grasp of Grousset's original masterwork ... uniquely great’. I have a blog post on ‘Grousset’s Tragic Jenghiz Khan’, why his portrait became the base material for mine. Few historians attempt a portrait of Chinggis/Genghis, and when they sketch in character they are inconsistent and confused; but Grousset should have been a novelist, he is a sensitive interpreter of the human glimpses in the sources, he has a grasp on character over time, over event. Elsewhere you can tell he’s a frustrated novelist in his biography of Chinggis, which has such evocative chapter titles as ‘Misery and Grandeur of the Nomads’, ‘The Tears of Chingis-khan’, ‘The Dogs of Chingis-khan eat Human Flesh’, ‘A Note of High Tragedy: Chingis-khan and Jamuqa’; I like this as a biography because it is stitched together from primary sources in straight or indirect quotation, little else.

These I have listed are old tomes; research-wise you have to go far past them and get up to date. Nevertheless I am wedded to old books, and old mind-sets and pre-twentieth-century observations shake us out of a too-contemporary outlook.

5. Robert E. Howard certainly tapped into the conflict between “civilized” vs “barbaric” cultures. As per the Excerpt below, you evoke these tensions too. Please discuss how those tensions affect your protagonists, Goatskin and Qi Miao.

My setting is perhaps the ultimate example in history of when the ‘barbarian’ side won over the ‘civilized’. At the last time that was possible, argues one world historian (David Christian). Except we’re on the eve of barbarian triumph. People forget how urbanised the steppe fringes were before Chinggis changed the tide on that; another historian (Paul Buell) says, further urbanised than at any time up until the advent of the railways.

And yes, I invoke the hell out of this conflict, these conflicting ways of life, in both my historical and my sword & sorcery. And guess whose side I’m on?

Goatskin lives on the eve of that great change; she lives to see it happen (I have a little story in NESS 5 called ‘The Change’, with her perspective at sixty); but for now she’s a downtrodden nomad living uneasily in a settled society. Her love Qi Miao is an ex-villager, as bandits almost exclusively were, and still has a bit of the village in her head when she thinks about nomads. That can cause them conflict on a personal level.

Civilization vs Barbarianism

"Civilized versus barbarian?” Goatskin cocked an ear. “That’s my life story.”

“It was the biggest manufacture of a panic we’ve been witness to. Poems hardened the lines, made a fetish of the wall. Tang culture had a craze for us, they famously loved exotica, we foreign merchants were in fashion, right up until we weren’t. The anti-foreign element won that old argument, conclusively it seems.” Nimgart curled his hands on his substantial hips. “It’s the damn poems run through my head when I look at this wall…" Waste Flowers p10

Since S.E.’s main interview series focuses on “Beauty in Weird Fiction”, let’s delve into Bryn Hammond’s hauntingly poetic style!

Beautiful Epic Army Battles With the Undead

"Slashing her ugly one-edged sword, she lopped flowerheads alongside limbs, burst flowers as well as organs. Purples streaked with gristle-white, they nestled where the hearts had been, fell garish in the Gobi sun, no splash of blood but spill of petals, and lay underfoot. Hacked flowers, raw crushed organs, trampled, and the salt a white clarity that got into her eyes to blur distinctions. Glistening organs, glittering salt, and the strong vivid sun that pierced, an investigative eye, into the anatomies of everything.

Who was to say which was precious, where lay beauty, the ugly organs, the viscera, the wilted ivy vine? The flowers didn’t care." Waste Flowers p23

6. Can you reveal more about the vegetative process/life as it relates to the undead in your books? I love this crossover of body horror and skeletal armies.

I might take this question as about the flowers that weave through Waste Flowers, from my corpse soldiers held together by an exuberant weed to my dead tribe of Jajirat who have ‘the beauty of pressed flowers’. My associations owe to the late Romantic poet Beddoes, with his imagery of flowers grown from graves as a communication from the dead to the living. Nobody offsets the charnel and the comic gothic with pathos like Beddoes, whose ‘dead are ever good and innocent, and love the living’ – it’s the living who are wicked. I did my English Honours on him. He was a scientist, an anatomist, a gay man, and in Germany a revolutionary; he never let go his disjointed, much re-written play Death’s Jest-Book, and killed himself at 45.

Waste Flowers was titled for Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil and Jean Genet’s Miracle of the Rose (or his other, Our Lady of the Flowers), who were the two influences I revisited before writing, to set my mood. The asethetics of Jean Genet were enormous for me when young, and still infuse me: he romanticised the worst people, he aestheticised his own time in prisons; he is the epitome of beauty in the gutter, and everything’s from life. In the passage you quote, Goatskin goes into a fugue state in battle and loses her sense of distinction between beauty and the ugly, between flowers and viscera. Genet taught me a lot of that. The ‘miracle of the rose’ is a rose grown in the heart of a murderer, whom the whole jail – in Genet’s telling – idolises and eroticises while in wait for his execution.

Baudelaire represents the whole Decadent thing that I was early in love with; I discovered them in the 80s through Dedalus Books’ range of end-of-the-nineteenth-century Decadent works, mostly from the French: Barbey d’Aurevilly, Huysmans of course; or through Mario Praz, his book The Romantic Agony on cruelty, and erotic cruelty, as a theme in late Romantic to Decadent writers. Later I added a lot more women, Rachilde, Jane de la Vaudère, largely translated by Brian Stableford, in big stacks from Snuggly Books.

Decadence is when Romantics took a late dark turn – champions of the same things, transgressive sex and crime like Byron’s Cain, gone further into the weeds of the lurid and the grotesque. I am certain Decadence fed into early sword & sorcery – writers like Clark Ashton Smith are simply Decadent themselves – and I’d love to explore that more. If anyone knows of scholarly treatment of those influences, do drop them in the comments.

7. Do you find beauty in your, or others’, weird fiction? Dissect an example.

My earliest weird fiction loves were Tanith Lee’s Flat Earth and M. John Harrison’s Viriconium. The weirdness lay in their sensibility for the dark side of beauty, or for a beauty of words splurged on unsavoury things. The later Viriconium tales intrigued me with almost a pain: take the squalid turn to Pastel City’s hero tegeus-Cromis in the story ‘The Lamia and Lord Cromis’. I fully identified with tegeus-Cromis in the early novel, and here he is decloaked, declined, and yet – the poignancy of that story, a kind of beauty you wince at. This sequence obsessed me, as unutterably profound.

Queerness was a big element in why I gravitated towards the Decadent from my young years. The longest poem I learnt by heart was the 300 lines of Swinburne’s ‘Anactoria’ – a poem for which he was ostracised, in the voice of Sappho abandoned by her lover Anactoria, steeped in sadistic imagery: ‘That I could drink thy veins as wine, and eat thy breasts like honey.’ Swinburne is notoriously about beauty and bewitchment of rhythm and word; meanwhile his chosen subject matter is often perverse loves and sympathetic crimes. The Engish Baudelaire – as preoccupied with lesbians but less pathologising: he throws himself into Sappho, he identifies with her (and he has his reasons; I, a lesbian, let him). ‘Perversity’ was a core word for me, in its layers of beauty, the weird, and the wrong.

A classic sword & sorcery work I’d cite is C.L. Moore, to whom I came late; the underworld journeys in her two Black God tales speak to me of subliminal things, tangled things that are as philosophical as they are horrific. I think these tales are dashed-off genius. Imagist sword & sorcery, symbolist sword & sorcery? I don’t know what to call them. But surface and depth, they have a beauty.

8. What scares you? Is it beautiful? That may seem deep, but we could rewrite that as “Do you see beauty in the things that terrorize Goatskin”?

My thrust in these novellas is rather where beauty and evil intertwine. I am not driven by fear so much as by questions of evil, and fascinated by conjunctions of beauty and evil. I spoke of Jean Genet: I was drunk on his vision of beauty in evil, written entrancingly.

In my second English Hons (because I dropped out and did my Honours year twice) I wrote on Dostoyevsky, ‘Saintliness and Perversity’: about how Dostoyevsky’s saints are always ex-criminals, and his criminals always potential future saints. To quote Poe, an ‘imp of the perverse’ can flip people between them (Dostoyevsky admired Poe; and ‘Imp’ was my fave story). My Tchingis Khan, late in his books, gained a few insights about his intimacy with evil; but there were things left to pursue. I mean to pursue them in my sword & sorcery. Where better? Ideas of evil are cultural of course, and What Rough Beast? delves ever deeper into Mongol conceptions of evil and an equivalent to saint’s work in a shaman’s, because there are things here too that rivet me with truths – truths to me. The me factor: I wrote essays on what mattered most to me (my tutors commented on this), and I write fiction by those personal lights too.

I have a history of writing monster point-of-view, with sympathy for them: an abandoned novel on Grendel (from which I rescued a poem, seen in Heroic Fantasy Quarterly); you might argue, my big attempt to intimately portray Tchingis Khan, who has been one of history’s monsters. So I’ve given Goatskin a strange thing whereby she experiences an intuition into monsters. It comes of her fascination. Like me, she often identifies with the monster.

9. Do you have any other artistic muses (singing, drawing, etc.), and if so, can we share any?

I like to slap oil paint on canvas. I make backgrounds; then they sit there and wait in vain for actual subjects; I hang backgrounds on my walls and a huge one sits on my easel next to the kitchen, I can look at it while I cook. Perhaps I like those possibilities open, perhaps I just like them to contemplate. I am helplessly drawn by colours, and creating the colours, mixing those lush oil paints into colours that enchant my eye, is the main game for me. Oh and let me not leave out textures: I love to thicken my paint with disused hair waxes and pastes, with ground-up shell from the garden shed, and slap it on with a trowel (strictly, a palette knife) in thick textures.

The only practical use I’ve found for my backgrounds is to photograph books on them for my blog or socials.

[caption id="attachment_515545" align="aligncenter" width="950"] [left] a three-layer background; [right] Pugmire’s Monstrous Aftermath on a background[/caption]

[left] a three-layer background; [right] Pugmire’s Monstrous Aftermath on a background[/caption]I adored Decadence in art and music, too. Moorcock’s Gloriana had a cover of Gustave Moreau’s Sappho, to start me. I got the libretto to Richard Strauss’ Salome, an opera after the Oscar Wilde play, and learnt to sing Salome’s last speech in German, adressed to the cut-off head of John the Baptist: I was passionately convinced the critics who called her depraved misunderstood; these lines were the truest truth, and her a saint for love.

By the way, genre was my road into these things, from the Moorcock cover on. I think it’s important to say, you can be a kid with no kindred interests in your family or social circles, and find this stuff out for yourself, with only genre fiction within reach to give you leads. Fantasy’s great that way; the erudite fantasy writers of old are eager to tell you who they draw on, and you can follow those threads into wonderlands undreamt, even if you’re stuck in the dullest neighbourhood with little intellectual curiosity around you.

Of course we have the internet now. If kids are allowed on it, into the future.

Expect Intimate Zombie Battles, as if George A. Romero created an ancient Chinese adventure!

…the two figures had entered by the only doorway to the room, and the arrow slit was its only air. Goatskin had to force her throat to gasp but she swung her ugly one-edged sword. Qi Miao crouched and tripped the walker over her spear. It wheeled its arms and sprawled back into the narrow light. At least Goatskin had not mistaken, in that first glimpse, its status as a corpse – seen her nightmare and not what was real. Flapping limbs to heave itself aright, awkward as a cockroach on its back, the light cut across its ribcage: exposed bone twined with ivy, and around its open belly ivy loops to hold the organs in. Beside the corrupt heart grew a big crimson flower" Waste Flowers p13

See all the books in the 'New Edge Sword & Sorcery Novellas' crowdfund on Backerkit (link)

Bryn Hammond

Bryn Hammond (she/her) lives in a seaside town in Australia with an enormous number of books, half of them about the steppe. Goatskin sword & sorcery novellas from Brackenbury Books: Waste Flowers, What Rough Beast? Her historical fiction series Amgalant closely follows the Secret History of the Mongols, a 13th-century life of Chinggis Khan. Voices from the Twelfth-Century Steppe is her craft essay. Work in ergot., Queer Weird West Tales, New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine, Beating Hearts & Battle-Axes.

Author Website https://amgalant.com/ and bookshelf . Find Bryn on Bluesky

S.E. Lindberg is a Managing Editor at Black Gate, regularly reviewing books and interviewing authors on the topic of “Beauty & Art in Weird-Fantasy Fiction.” He has taken lead roles organizing the Gen Con Writers’ Symposium (chairing it in 2023), is the lead moderator of the Goodreads Sword & Sorcery Group and was an intern for Tales from the Magician’s Skull magazine. As for crafting stories, he has contributed eight entries across Perseid Press’s Heroes in Hell and Heroika series, has an entry in Weirdbook Annual #3: Zombies. He independently publishes novels under the banner Dyscrasia Fiction; short stories of Dyscrasia Fiction have appeared in Whetstone, Swords & Sorcery online magazine, Rogues In the House Podcast’s A Book of Blades, DMR’s Terra Incognita, and the 9th issue of Tales From the Magician’s Skull.

.jpg)