Simulcast on Black Gate: BEAUTY AND NIGHTMARES ON ALIENS WORLDS: INTERVIEWING C. S.FRIEDMAN

We have an ongoing series at Black Gate on

the topic of “Beauty in Weird Fiction” where we corner an author and query them

about their muses and methods to make ‘repulsive’ things ‘attractive to

readers.’ Previous subjects have included Darrell

Schweitzer, Anna

Smith Spark, Carol

Berg, Stephen

Leigh, Jason

Ray Carney, and John

C. Hocking (see the full list at the end of this post).

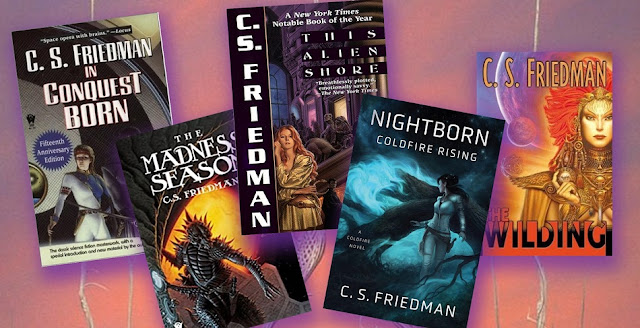

Inspired by the release of Nightborn: Coldfire

Rising (July 2023, see Black

Gate’s review for more information), we are delighted to interview

C.S. Freidman! Since the late 1990’s she has established herself as a

master of dark fantasy and science fiction, being a John W. Campbell award

finalist and author of the highly acclaimed Coldfire trilogy

and This Alien Shore (New York Times Notable Book of

the Year 1998).

Let’s learn about C. S. Friedman’s muses & fears, her

experience with art, and tease a future TV series!

SEL: Tell us about your fascination with Human vs Alien

Colonization, and the struggle over shared souls/minds/psyches. That foundation

resonates across This Alien Shore, The Madness Season (the

Tyr’s gestalt-mind), the Coldfire series (via the ethereal

fae), and the Magister Trilogy (consumable souls!).

CSF: Science fiction and fantasy offer an opportunity for us

to step outside of our normal human perspective, questioning things we normally

take for granted. What better vehicle could there be for this than to have

humans confront a non-human being or force? Or to have two souls battle

over a single identity? Such stories invite us to question what

‘identity’ really means, and whether the assumptions we make about the world

are rooted in some kind of universal reality, or are simply a human construct.

One of my favorite creations is the first story I decided to

publish, which wound up being chapter 11 in my first book, In Conquest

Born. Stranded on an alien world, a human telepath is forced to seek

mental communion with an alien race. In doing so, she must surrender her

human identity, because the manner in which these aliens perceive the world is

not something a human psyche can comprehend. One must see reality through their

eyes to understand them. That is a repeated theme in my work.

One of my favorite stories that someone else wrote was

published many years ago in Asimov’s SF magazine. It was Nancy Kress’s “A

Delicate Shade of Kipley.” It takes place on a world where constant fog makes

everything appear gray, so that the entire world is drained of color. The

humans who landed there desperately hunger for color and treasure the few

colorful pictures of Earth that they have managed to salvage. To their

child who was born there, however, the grey world has its own kind of beauty,

and she relishes fine gradations of gray as her parents once relished the

brilliant colors of a rainbow. (“A Delicate Shade of Kipley” can be found in Isaac Asimov: Science Fiction

Masterpieces)

Jeszika Le Vye’s cover for Nightborn prominently

features the fae even more so than the striking trilogy covers by Whelan (more

on those below); we learn in the novella Dominion (bundled

with Nightborn) that the fae has colors (to those blessed to see

them). The alien energy seems to be both muse and nightmare, and we’d love to

learn your take on them. Do you envision your own nightmares and muses this

way?

No, my nightmares are much more mundane. The most terrifying

ones involve the American Health Care system 😊.

The fae is described: Earth-fae is a luminescent blue, dark

fae the intense purplish glow of a UV lamp, solar fae gold. One of the

opening scenes in Jaggonath takes place when an earthquake hits, and the wards

on buildings pulse with visible blue power. The fae is beautiful and

energizing and terrifying, all at once.

I was thrilled to find some pictures of bioluminescent ocean

waves while I was working on Nightborn. No doubt my cry of “Oh my

God, it’s the fae!” could be heard for miles. The eerie beauty of rippling blue

light as it ebbed and flowed with the waves was mesmerizing, and that will be

my image of it forever, now that I have found those videos (here’s a link to sample

them).

The Coldfire Series,

cover art by Michael Whelan

What scares you? Is it beautiful?

“I was afraid that if I became a happier person I would

not be able to write dark fiction” — C.S. Friedman

What scares me most is the darkness in my own soul, the

capacity for depression that can cause me to sabotage my own life and undermine

my own spirit. The only thing positive I will say about it is that I drew upon

my experience with depression in my early books when I depicted psychological

darkness. In fact, I recall when I was first diagnosed and offered

anti-depressants, I was afraid that if I became a happier person I would not be

able to write dark fiction. And it is harder now, to be sure.

There is a song by the band Renaissance, Black Flame. It

tells the story of someone struggling against inner darkness, in powerfully

evocative poetry. For me it has always reflected that terrible inner

seduction, the darkness that can drive a human soul to lose sight of its path,

and ultimately destroy itself. Here is the song on Youtube, and

here are the

lyrics.

Here

is another piece they did in which psychological darkness becomes

hauntingly beautiful. (A radio contest declared it “the most depressing

song ever.”). I believe the original music is by Bach.

There is a dark beauty in such songs, and I hope in my

writing.

Do you detect beauty in art/fiction that appears to be

repulsive (weird/ horror)? Any advice for writers on how to strike the

right balance to keep readers engaged?

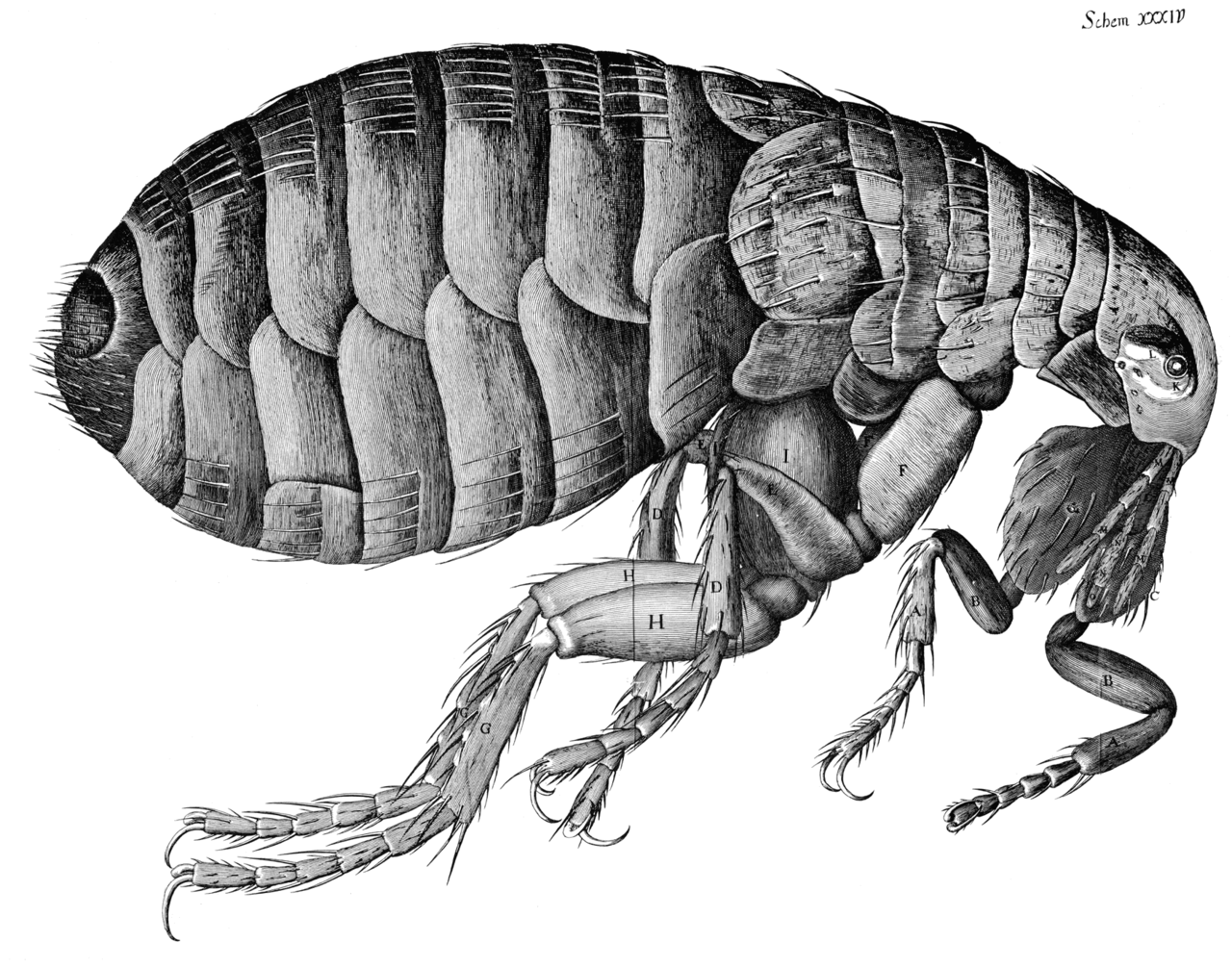

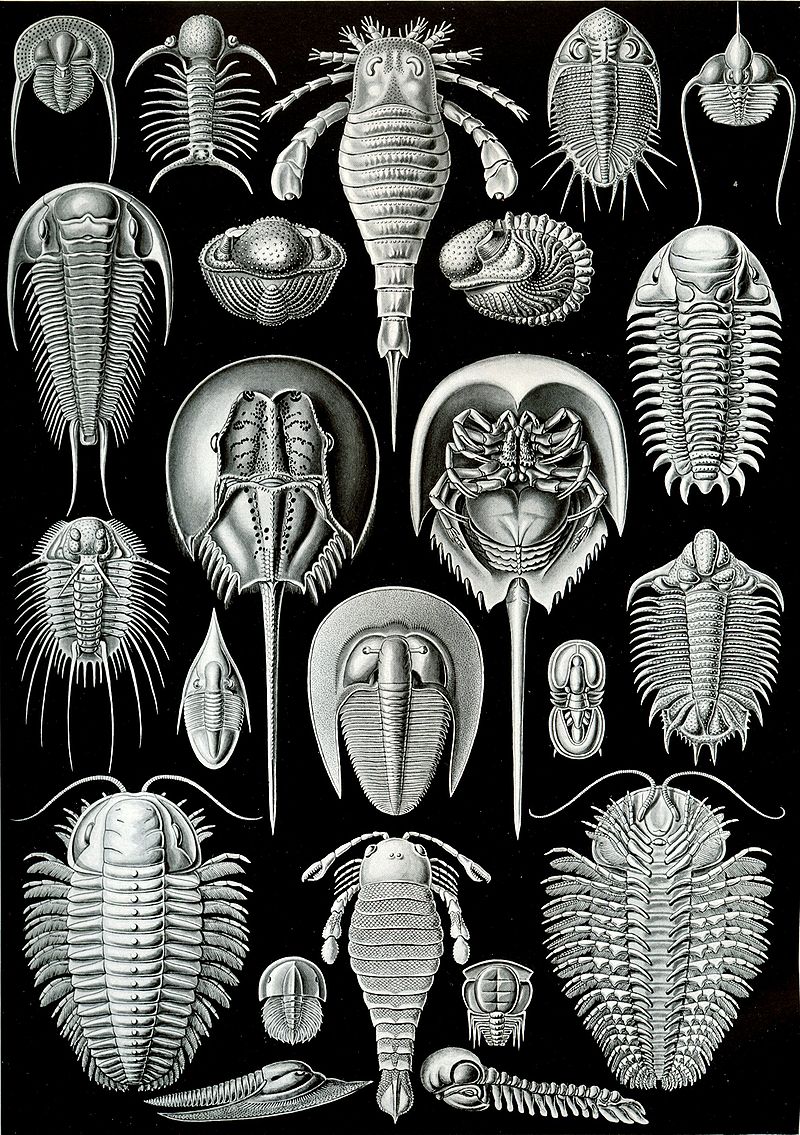

What is beauty? Is it something that is “pretty?” or a

deeper, more visceral quality? Classically beautiful things transfix us, but we

will also stop at the site of a road accident, mesmerized by its horror.

Against our will, we want to see it.

Gerald Tarrant is the essence of human beauty, described as

nearly angelic in appearance. When he walks through a room, everyone notices

him, and women are magnetically drawn to him. But it is the horror of that

appearance being wedded to pure evil that makes us want to read about him —

that makes it impossible for us to look away. It is when the nature of

something horrific fascinates us that we cannot turn our eyes away, no matter

how much we want to.

“… it is the horror of that appearance being wedded to

pure evil that makes us want to read about [Tarrant].” – C. S. Friedman

Fashion Muse: You were formerly trained in Costume Design [link]),

creating for professional theater, PBS, and all sorts of productions; you even

were a lecturer on the topic for years. Do you still dabble in fashion arts,

and how does that influence your prose and/or character design?

Not really. I was in an abusive job situation for 13 years

and I burned out pretty badly. Knowledge of aesthetic principles and fashion

history inform my descriptions, of course, but I have left that field behind in

favor of writing and teaching. Sometimes I miss it, but what I miss is the

pleasure I originally took in it, not what it became. There are too many bad

memories now. I sew when I have to, not for pleasure.

What other muses inspire you (i.e., for your bead jewelry [link]),

and does that creativity spill over to writing?

I took up glasswork because it was different from my

writing, using different parts of the brain, explorations of color and texture

rather than language. It speaks to a different side of my creativity, which

is why I enjoy it.

Do you identify with your protagonists?

No, and sometimes I feel like I am unique among writers in

not having a personal connection to my characters. I have been on writing

panels where writers talk about how they talk to their characters, or sense

what their characters want to do…I just write them. They are my creations. I

relate to them as I would relate to clay I was molding into a sculpture, or

glass I was wrapping around a mandrel. I am deeply invested in them as

creations, but not as people.

The Magister Series –

cover art by John Jude Palencar

Let’s talk about covers & how artists depict your

characters via illustrations. Gerald Tarrant was famously adapted in the

Michael Whelan cover for the Coldfire trilogy) and Kamala from the Magister

Series depicted by the renowned John Jude Palencar. Traditionally,

authors have no say in the cover art design, but I’m curious about your

experience. Did the costume designer in you have any influence or comment on

those?

I have been permitted to offer input into my covers, to

varying degrees. This is something that evolved over time. I studied graphic

art in college, and of course I spent years as a theatrical designer, so I have

enough understanding of graphic design to offer meaningful input, and I have

always understood that the purpose of a cover is to help market the book. Over

time, my editor learned that I could offer meaningful suggestions in that

context, so I have been allowed to do so.

Any current or future endeavors we can pitch? More Coldfire? In August

2022, Deadline reported The Coldfire Trilogy may

become a TV series; also according to Pat’s

Fantasy Hotlist, you have plans for another Coldfire novella

will be focused on Gerald Tarrant bringing faith to his world, even as darkness

begins to take root within his own soul.

The most exciting news right now is my novel Nightborn, which

is coming out in July. It tells the story of the founding of Erna and

mankind’s discovery of the fae, and is one of the most intense things I have

ever written. That volume will also include Dominion, a novella

dealing with Tarrant’s transformation from a simple creature of the night into

the Hunter. Both are compelling works that I know Coldfire fans

will enjoy, but also accessible to new readers.

And yes, we are attempting to market a TV series based

on Coldfire, so fingers are crossed on that. I want to see

the fae in visual media! The next novel will probably be in my Outworlds series

(This Alien Shore, etc.) but I am considering shorter works in the Coldfire series.

There are so many interesting time periods and events in Ernan history! I

am working on a timeline that will enable me to offer many different stories,

all in the context of the greater setting. It’s all very exciting, and the

enthusiasm my fans have shown for all my Coldfire stories

has been downright inspiring.

“And yes, we are attempting to market a TV series based

on Coldfire, so fingers are crossed on that. I want to see

the fae in visual media! ” – C. S. Friedman

Lots of updates are forthcoming! How do we stay in touch

with the latest?

Please join me on Facebook, and/or Patreon for news, essays,

project excerpts, and of course conversations with my readers.

C.S. Friedman

An acknowledged master of dark fantasy and science fiction

alike, C.S. Friedman is a John W. Campbell award finalist, and

the author of the highly acclaimed Coldfire trilogy, This

Alien Shore (New York Times Notable Book of the

Year 1998), In Conquest Born, The Madness Season, The

Wilding, The Magister Trilogy, and the Dreamwalker series.

Friedman worked for twenty years as a professional costume designer, but

retired from that career in 1996 to focus on her writing. She lives in

Virginia, and can be contacted via her website, www.csfriedman.com, Facebook,

or Patreon.

#Weird

Beauty Interviews on Black Gate

- Darrel

Schweitzer THE

BEAUTY IN HORROR AND SADNESS: AN INTERVIEW WITH DARRELL SCHWEITZER 2018

- Sebastian

Jones THE

BEAUTY IN LIFE AND DEATH: AN INTERVIEW WITH SEBASTIAN JONES 2018

- Charles

Gramlich THE

BEAUTIFUL AND THE REPELLENT: AN INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES A. GRAMLICH

2019

- Anna

Smith Spark DISGUST

AND DESIRE: AN INTERVIEW WITH ANNA SMITH SPARK 2019

- Carol

Berg ACCESSIBLE

DARK FANTASY: AN INTERVIEW WITH CAROL BERG 2019

- Byron

Leavitt GOD,

DARKNESS, & WONDER: AN INTERVIEW WITH BYRON LEAVITT 2021

- Philip

Emery THE

AESTHETICS OF SWORD & SORCERY: AN INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP EMERY 2021

- C.

Dean Andersson DEAN

ANDERSSON TRIBUTE INTERVIEW AND TOUR GUIDE OF HEL: BLOODSONG AND FREEDOM! (2021

repost of 2014)

- Jason

Ray Carney SUBLIME,

CRUEL BEAUTY: AN INTERVIEW WITH JASON RAY CARNEY (2021)

- Stephen

Leigh IMMORTAL

MUSE BY STEPHEN LEIGH: REVIEW, INTERVIEW, AND PRELUDE TO A SECRET CHAPTER (2021)

- John

C. Hocking BEAUTIFUL

PLAGUES: AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN C. HOCKING (2022)

- Matt

Stern BEAUTIFUL

AND REPULSIVE BUTTERFLIES: AN INTERVIEW WITH M. STERN (2022)

- Joe

Bonadonna MAKING

WEIRD FICTION FUN: GRILLING DORGO THE DOWSER! 2022

- S.

Friedman. Beauty and Nightmares on Aliens Worlds 2023

- interviews

prior 2018 (i.e., with John R. Fultz, Janet E. Morris,

Richard Lee Byers, Aliya Whitely …and many more) are on S.E. Lindberg’s

website