This post originally appeared on the Once and Future Podcast website on Sept 3rd 2018.

Reposting here since that website is now sun-setted.

Embedded Images are all under Public Domain or Common License:

The Elusive, Inspirational Soul – by S.E. Lindberg

For most artists, including writers, the act of creating

attempts to capture and share some emotion, or conversely, evoke an emotional

response from an audience. Often, we draw inspiration from our past experiences,

traumatic or enjoyable, to deepen the impact. As a scientist, I find the entire

transaction of emotions oddly inspirational and terrifying. Feelings are

ubiquitous, but cannot be measured objectively; they do not seem to adhere to

any law of conservation like energy or mass obey (is there any limit to sorrow

or joy?).

Could we better our craft if we knew how emotions flowed

from an object (fine art or prose) to a person (or vice versa)? Let us examine the

sources and sinks of emotion: our souls. In playful art, this is quite easy to

simulate; heck, consider the soul-currency for crafting in From Software’s Dark Souls videogame series—if only we

could see as the undead do! In real life, studying the soul is harder.

Many ‘Renaissance Men’ were

inspired to find the soul while the art of anatomy flourished. The prevailing

Church did not permit the dissection of innocent believers, so criminals or ‘sinners’

were often studied. Bodies were

considered divinely sacred and were thus difficult to obtain; acceptable corpses

could not be refrigerated, so one had to work fast. Nor were there

cameras or video to capture the observations, so artists and alchemists convened

in the dissection theaters to document the microcosms of life. Leonardo

Da Vinci provided detailed notes along with his drawings (from The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci. Oxford

World's Classics, 1998):

"I have dissected more than ten human bodies, destroying all the various members and removing the minutest particles of flesh which surrounded these veins, without causing any effusion of blood other than the imperceptible bleeding of the capillary veins. And as one single body did not suffice for so long a time, it was necessary to proceed in stages with so many bodies as would render my knowledge complete; this I repeated twice in order to discover the differences. And though you should have a love for such things you may perhaps be deterred by natural repugnance, and if this does not prevent you, you may perhaps be deterred by fear of passing the night hours in the company of these corpses, quartered and flayed and horrible to behold; and if this does not deter you, then perhaps you may lack the skill in drawing, essential for such representation..." p151

Da Vinci determined that the senses were linked to a ‘common

sense’ that led to the brain. But no actual soul was discovered. He yielded

the goal of managing the soul to religion. Below, from his treatise

on painting, he spoke how the artist must deal with this and impart the soul

into its subjects otherwise:

Anatomical

artists had to grapple with documenting macabre scenes of opened bodies while

remaining 'artistic'. For the dignity of the

specimens and to satisfy the surgeons' needs, artists often found harmony by

posing their subjects. Perhaps most famous are Johannes de Ketham's Fasiculo de Medicina (1491), Andreas

Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543),

and Leonardo Da Vinci's notebooks (1500). The contemporary Bodies:

The Exhibition continues this

controversial tradition of displaying the dead artistically.

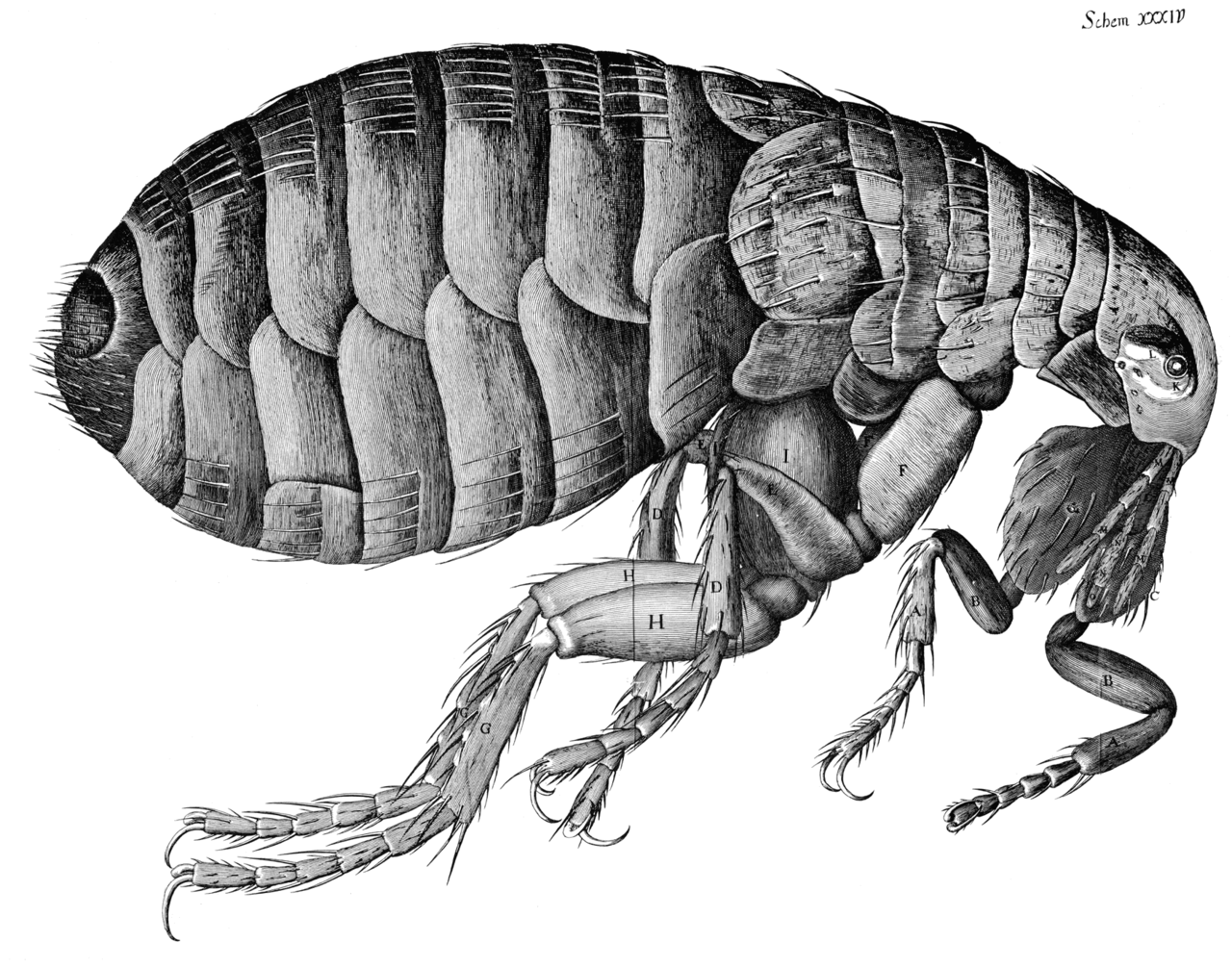

With the most promising connection to our souls being the senses, it follows that the next great promise of discovery came when optical technology allowed scientists to see new worlds. Pioneering microscopists had to draw their observations. In 1664, Robert Hooke published a large treatise entitled Micrographia or Some Physiological Description of Minute Bodies, containing an encyclopedia of detailed drawings of his microscopic views. In his preface, he explains to the reader that optics have enabled a spiritual quest:

“… by the help of

microscopes, there is nothing so small, as to escape our inquiry; hence there

is a new visible world discovered to the understanding. By this means the

heavens are opened, and a vast number of new stars, and new motions, and new

productions appear in them, to which all the ancient astronomers were utterly

strangers.”

The

soul has never found, however. Despite ‘the opening of heaven’ with

microscopes, the soul still eludes us.

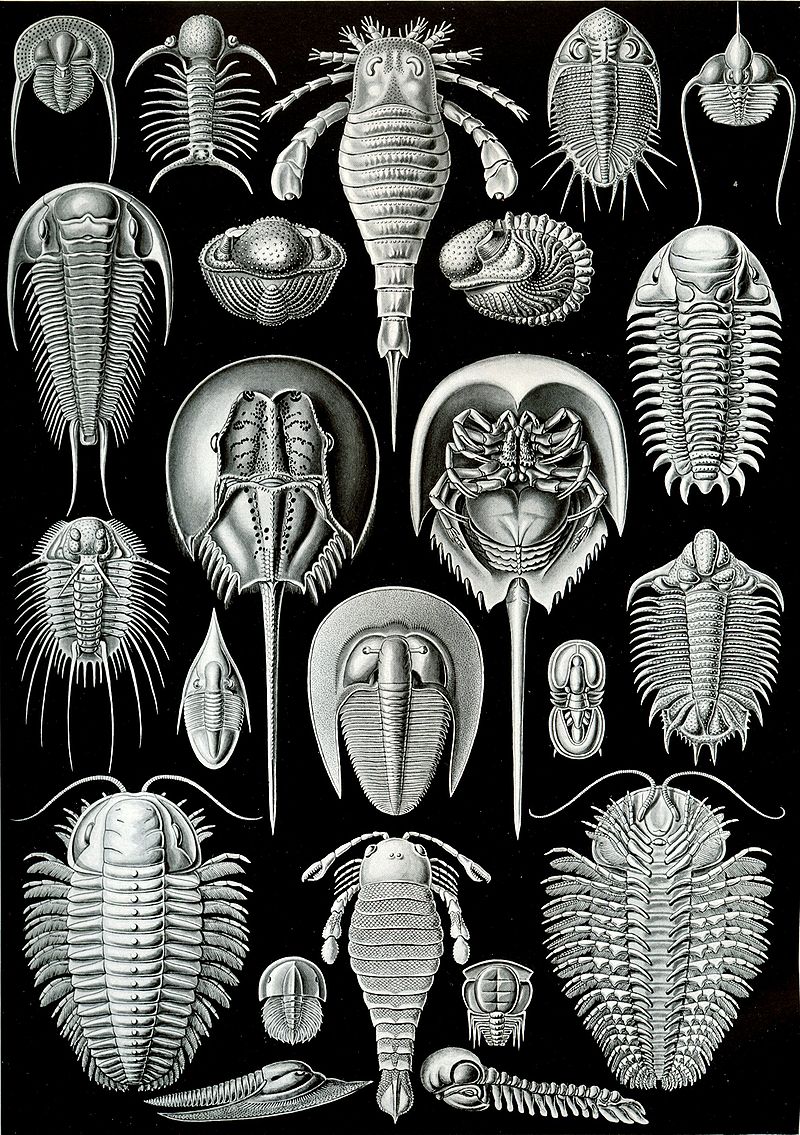

Ernest Haeckel

(1834-1919) was another famous artist-scientist fascinated with the aesthetics

of nature and the elusiveness of the soul. His 1904 set of lithographs Art Forms in Nature brilliantly exhibit

his obsession with the symmetrical beauty of biological microstructures, and

his extensions into comparative embryology brought him controversy. He argued

this in his support of his own monistic religion that scientific adventures

continually uncovered the beautiful designs inherent in nature (monism

generally supports that ‘body and soul’ are one connected entity, not separate

as many dualistic religions profess):

“The remarkable expansion

of our knowledge of nature, and the discovery of countless beautiful forms of

life, which it includes, have awakened quite a new aesthetic sense in our generation,

and thus given a new tone to painting and sculpture. Numerous scientific

voyages and expeditions for the exploration of unknown lands and seas, partly

in earlier centuries, but more especially in the nineteenth, have brought to

light an undreamed abundance of new organic forms... affording an entirely new

inspiration for painting, sculpture, architecture, and technical art.”

In 1900, Haeckel

published his scientific, spiritual book Riddle

of the Universe at the Close of the Nineteenth Century in which he explains

his monistic philosophies. He shares elegant philosophy on the soul's

lack of participation in the "Laws of Substance" (conservation of

mass and energy); below, he discusses how many related the nonexistent soul to

that which is tangible:

“Thus invisibility comes

to be regarded as a most important attribute of the soul. Some, in fact,

compare the soul with ether, and regard it, like ether, as an extremely subtle,

light, and highly elastic material, an imponderable agency, that fills the

intervals between the ponderable particles in the living organism, other

compare the soul with the wind, and so give it a gaseous nature; and it is this

simile which first found favor with the primitive peoples, and led in time to

the familiar dualistic conception. When a man died, the body remained as

a lifeless corpse, but the immortal soul ‘flew out of it with the last breath.’”

Indeed,

the many myths of preserving a dead man’s soul, or gaining its powers, is

pervasive. The notion of relics is common across cultures and time. It assumes

that the soul is a contagion remaining attached to the body postmortem. Hence,

the power of a Saint could be absorbed if one obtained his or her bones; this

gave rise to the theft and desecration of many crypts and catacombs. Many

crypts remain with the bodily relics on display. The crypt of Saint Munditia of

Munich and the Vienna Imperial Crypts are fine examples. Other famous examples

include the shrines of Capuchin monks in Rome and Palermo, Sicily (>6,000 bodies)

and the Kostnice 'Church of Bones, Kutna Hora, Sedlec Ossuary, Prague (~40,000 remains).

Alas,

we cannot study the soul directly yet, but the journey is inspirational. H.P.

Lovecraft summarized our human condition best in his opening to “The Call of

Cthulhu” (Weird Tales, 1928):

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age…”

S.E.

Lindberg resides near Cincinnati, Ohio working as a

microscopist, employing scientific and artistic skills to understand the

manufacturing of products analogous to medieval paints. Two decades of

practicing chemistry, combined with a passion for dark fantasy, spurs him to

write graphic adventure fictionalizing the alchemical humors (primarily under

the banner “Dyscrasia Fiction”). With Perseid

Press, he

writes weird tales infused with history and alchemy (Heroika: Dragon Eaters, Pirates

in Hell). He co-moderates the Sword & Sorcery group on

Goodreads.com (please

participate), and regularly interviews authors on the topic of Beauty in Weird Fiction.